With each succeeding year, the producers of the school play feel an urge to break new ground, to make the next year's play one in a modern setting - perhaps even a comedy.

|

But to undertake such a venture with a society of seasoned actors is one thing; to attempt it with a group of enthusiastic but inexperienced young actors is quite another. Every year fifth or sixth formers from the previous year's play leave the school and new actors must be sought after to replace them.

These must be 'broken in', as it were. It is impossible to expect them to act in comedies or even plays set in modern times, as those tend to be much more demanding both from an acting and casting point of view. Historical characters tend to be more remote from the audience than present day characters if only because they represent a remote age. The audience is more alive to flaws in the character of a twentieth century man because he must be portrayed more accurately and precisely than, say a fifteenth century man, because he is, so to speak, one of us. The part of a fifteenth century man can be treated a little more liberally, and with less accent on accuracy to detail, because nobody in the audience is aware of the details of character of such a man.

Female parts also present a difficulty, but are quite feasible in an historical play; in a modern play well-night impossible.

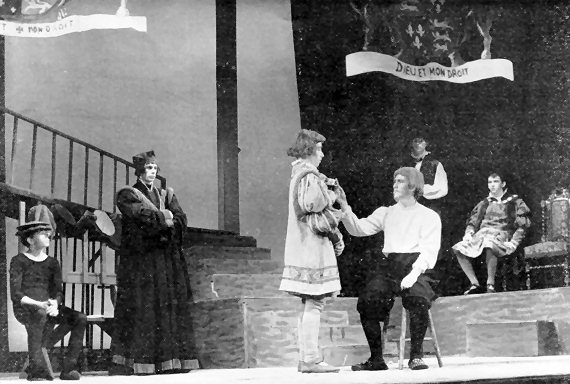

However, this is all by the way. Robert Bolt wrote, "Man for All Seasons."' - a nice safe historical play about Sir Thomas More; by far the most difficult and certainly the best play yet presented, that is to say, best as far as its authorship was concerned; about the acting I am not qualified to say.

It was a great play to act in. No member of the audience, however quick or intelligent, could hope to appreciate it fully, even if he or she came each and every night. There were points in it we were seeing for the first time, at quite an advanced stage in rehearsals.

As usual, we began rehearsals well before Christmas. And yet no matter how early we start, there still seems to be so little time to spare at the end. We always wonder if it will ever get off the ground. At first we had little difficulty. Our most unsure moments were up on the rather rickety platform and wooden slope that Mr. Tufnell had erected to "give us the feel of the thing."

I remember galloping down there at a mile a minute one time and nearly braining a lad when I knocked off a loose plank.

|

We had the usual number of rehearsals, after school, in lunch hours and on half holidays, the inevitable one on January 6, the day before we go back after Christmas, usually; when everybody looks forward to a nice quiet warm afternoon by the fire, what do we have to do? Only wend our weary way schoolwards, in all weathers and any weather, wondering what mad ambition drove us into the school play, and cursing nobody in particular and everybody in general. Those are the worst times. And even at the worst times we only curse the producers in the nicest kind of wav. At the best of times we laugh and joke and wonder how we shall ever present this fearful bedlam, which is a rehearsal, to the critical eye of a Harrow audience. |

"Allow me to say, Sir Thomas . . . .”

"Get outa me way, can't see the Mayor." (Laughter all round).

"Allow me to say, Sir Thomas, for the second time," (more laughter) "how honoured I am to be here in this proud moment! Ah, here's Will Roper now." No Will Roper. (More loudly) "Ah, here's Will Roper now!" Still no Will Roper. (At the top of his voice) "I said (pause) "Ah" (pause) Here's - Will - Roper - now!" Enter Will Roper, puffing like a winded grampus.

At this point, the producers, hitherto a study in long-suffering and injured patience (mutilated, in fact), decide it's time they had something to do with their play.

"Enter, clown!" echoes from the floor with amazing clarity, and with great sarcasm.

Will Roper casts what he hopes is a scathing glance in the direction of the producer's chair, and retires from the scene with an air of injured innocence.

| How may threats and ultimatums came from the said chair nobody bothered to count, mainly because nobody took a blind bit of notice of them, most people irreverently regarding the producers as ornamental figures in classic postures (sitting postures, usually) draining an unending quality of coffee from little blue staff-room cups, and making untimely interruptions with "invaluable" advice or encouraging the cast by telling them in many ways and giving them umpteen good and varied reasons why the play should never be produced, much less be the resounding success everybody hopes for. (I hope I can persuade Mr. Crawford and Mr. Tufnell, our long-suffering producers, that that last sentence was all a joke or a misunderstanding). |

|

This happily, is a very cynical view, and even more happily for me, nobody takes it seriously - at least I hope nobody takes it seriously - and it would only embarrass them if this turned into a wholesale tribute to all their good work (and all our co-operation).

The errant Will Roper did, in fact, come puffing on like a winded grampus on the first night and, being sadly out of breath, late on cue, and much exhausted by that cruel climb from the dressing room in full regalia, could only, when it was time for his line as he rushed wildly in, he could only, as I say, croak to the world at large, much to the dismay of his fellow actors waiting patiently for him with nothing to say and nowhere to go, and much to the amusement of the stage crew in the wings. The said panic-stricken entrance of poor Will was a cause for much controversy ever after, and nobody really knows how many people noticed, if anyone noticed, or how much they noticed. What is certain is that whenever our gallant hero-cum-grampus asks anybody what night they saw the play, he shudders inwardly, and, who knows, outwardly, if they say "Wednesday".

Chris Clubbe competently handled the lead part, a tough and demanding role, since he was rarely off stage, and rarely with nothing to say, during the whole performance.

Silver tremendously effective as Thomas Wolsey, looking for all the world like a big black cat, whether that is a compliment or not I don't know.

|

Ferry, in his first big part - his first part at all, I think, did wonderfully well in a difficult part - trying to act a beautiful girl looking intelligent at the same time. Welling had the tremendously demanding job of holding the play together as the Common Man. It was with some trepidation that the producers gave such a part to so young a boy. However, Welling was perhaps the greatest success of the play, particularly in providing the comic relief necessary in the midst of a long, involved, intellectual argument. Did anyone notice the plastered, broken forearm of the Common Man - camouflaged in black paint? |

The play did come out on time after all, either thanks to or in spite of us, and that after dress rehearsals, photo calls, and the customary preview to the school across the road. That's the worst ordeal of all. Trying to act in front of a hall full of giggling females is enough to make you tear your wig. They laugh where nobody's ever laughed before, and if they are ever so misguided as to let out an involuntary snigger at some doubtful joke, a sharp "ssh!" is heard from the back row where a line of stern-faced nuns are keeping a sharp eye on their charges. Audiences are a funny crowd. They are either good or bad, and when they're good they're very good and when they're bad it’s like acting to an empty hall.

Anyway, it was great fun - as it always is, and I will always contend that it can be fitted in to the school year quite satisfactorily without in any way affecting school work. I always think that if I did not act in the play I'd probably waste just more time doing something far less worth while.

Edward O'Gorman, L.6.